Two “Population Billionaires”

30 Apr, 2023

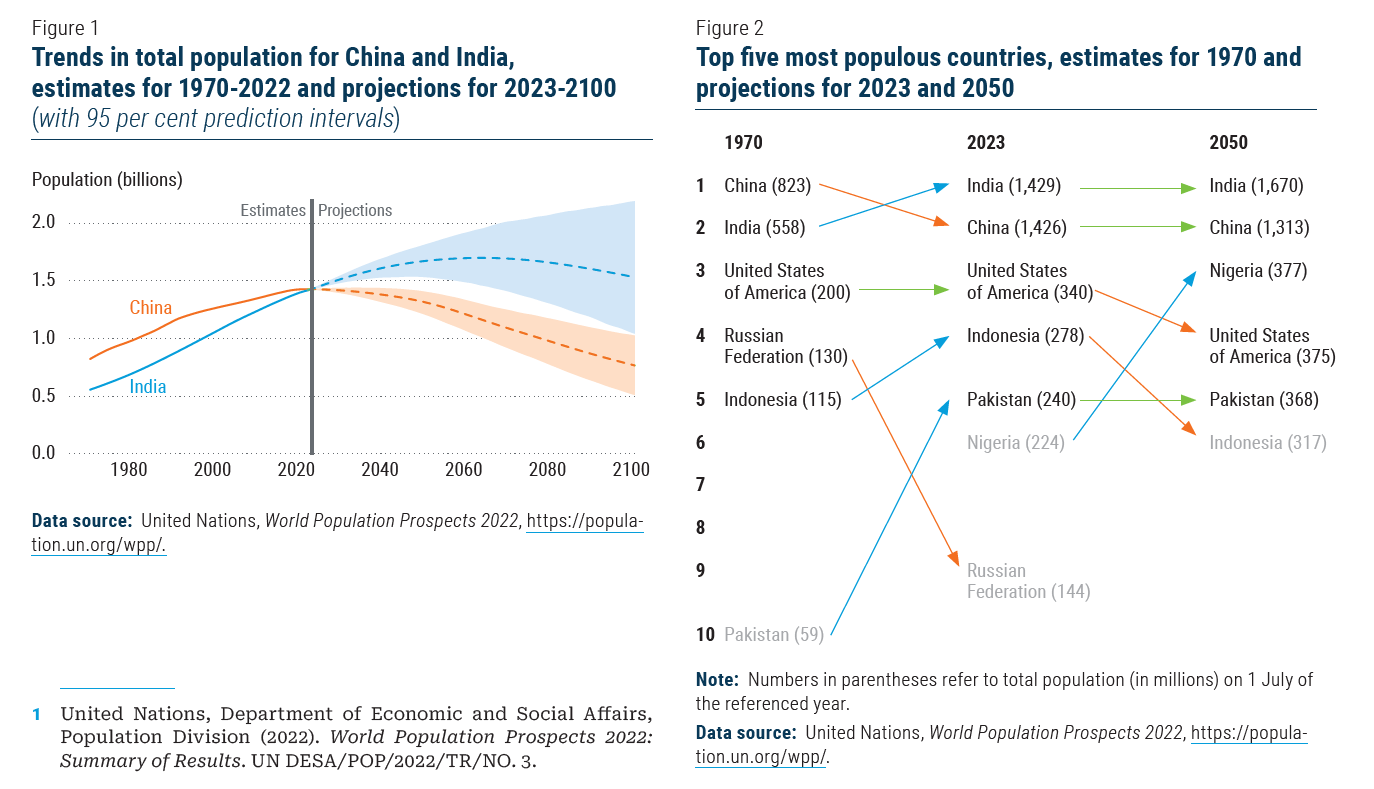

In April 2023, India’s population is expected to reach 1,425,775,850 people, matching and then surpassing the population of mainland China (figure 1).

India’s population is virtually certain to continue to grow for several decades. By contrast, China’s population reached its peak size recently and experienced a decline during 2022.

Many factors contributed to falling birth rates in China and India, but the relative contributions of each remain a matter of debate (Bongaarts and Hodgson, 2022).

Population policies in China

During the second half of the twentieth century, both countries made concerted efforts to curb rapid population growth through policies that targeted fertility levels.

In China, the most notable policies were the “later, longer, fewer” campaign of the 1970s, which promoted later marriage, longer intervals between births and fewer children overall, as well as the stricter “one-child” policy, in effect from 1980 until 2015, which limited couples to one or two children with some exceptions (Wang and others, 2016).

These policies, together with investments in human capital, changing roles for women and other factors, contributed to China’s plummeting fertility rate in the 1970s and to the more gradual declines that followed in the 1980s and 1990s.

Population policies in India

India also enacted policies to discourage the formation of large families and to slow population growth, including through its national family welfare programme beginning in the 1950s.

However, under India’s federal structure, state governments were able to set their own policy priorities, resulting in varied impacts across different parts of the country.

In Kerala and Tamil Nadu, where state governments emphasized socio-economic development and women’s empowerment, fertility declined earlier and at a more rapid pace, falling below the replacement level two decades before the country as a whole.

Those states that invested less in human capital, especially for girls and women, experienced slower reductions in fertility, despite controversial mass sterilization campaigns and other coercive measures in some locations (Gupte, 2017; May 2012).

India’s lower human capital investment and slower economic growth during the 1970s and 1980s, contributed to a more gradual fertility decline compared to China and, consequently, to more rapid and persistent population growth.

Older persons

The number of older persons is growing rapidly in both China and India. This growth is linked to increasing numbers of births around the middle of the last century, as those cohorts are now reaching older ages, and to falling mortality risks that allow more people to survive to advanced ages. Between 2023 and 2050, the number of persons aged 65 or over is expected to nearly double in China and to more than double in India, posing significant challenges to the capacity of healthcare and social insurance systems.

By 2040, persons aged 65 or over in China will outnumber those under age 25; and by 2050 they could comprise 30 per cent of the total population (figure 5). Countries like Japan and the Republic of Korea have experienced similar rapid population ageing, but at higher levels of economic development than has been achieved in China. In India, the ratio of older persons to those of working age is expected to remain lower than in China, reflecting the slower pace of population ageing in India.

Planning for and adapting to demographic change

Together, China and India are home to more than one third of the world’s population. For many decades, the size and growth of the Chinese and Indian populations have been a focus of global concerns about the rapid growth of the human population and its implications for sustainable development (United Nations, 2022c).

Meeting people’s needs in these two largest countries is critical for the world to achieve the Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and for ensuring that no one is left behind.

To eliminate poverty and improve well-being, India’s youthful population requires scaled-up investments in health and education and enabling conditions for productive and sustainable employment.

Meanwhile, both countries should commit to social protection and other measures to secure the health and well-being of growing numbers of older persons.

All countries must ensure that policies and programmes aimed at influencing fertility level are grounded in principles of reproductive rights, ensuring that all individuals and couples are free to decide how many children to have and when to have them, and that they have the information and means to do so.

Family-friendly policies that provide support to parents and promote gender equality within households can ease some of the challenges of childrearing, especially for working women, and help people to have the number of children they desire.

The success of global efforts to ensure environmental sustainability will depend critically on developments in China and India.

As both countries continue to pursue sustained economic growth and prosperity for their people, it is essential that increasing per capita incomes do not undermine efforts towards more sustainable consumption and production.

To protect and preserve the planet for future generations, the economies of the two countries – and of the world – must urgently transition away from the current overdependence on fossil-fuel energy.

Authors: Sara Hertog, Patrick Gerland and John Wilmoth, UN DESA Population Division.

Original Article: UN DESA Policy Brief No. 153: India overtakes China as the world’s most populous country

PDF document available at:

https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/PB153.pdf